Inquiry

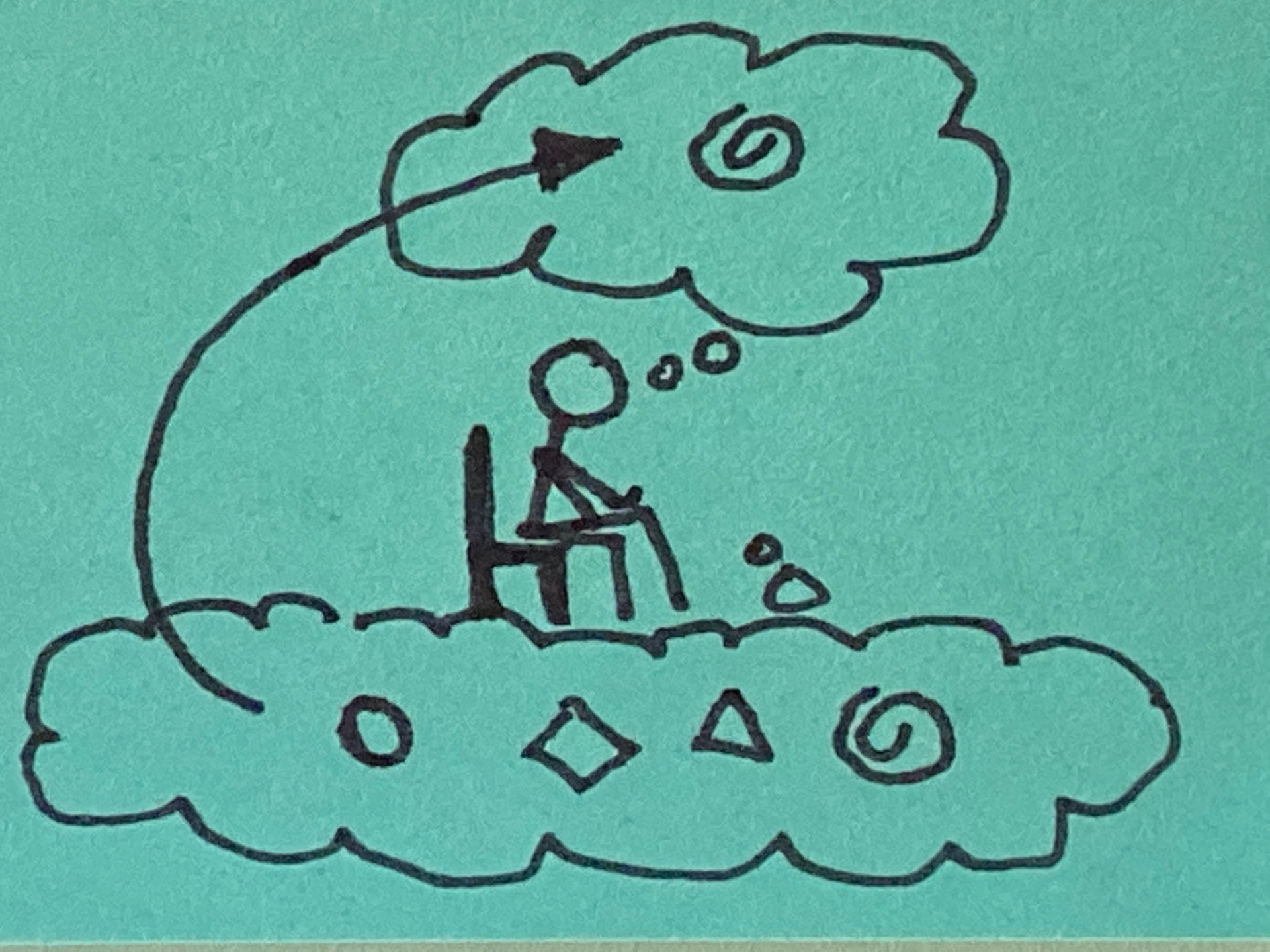

Explore your senses and emotions, and access the subconscious knowledge they provide.

according to Discernment, it’s important that we be able to listen to and interpret our inner “complex of feelings” in the moment, with subtlety and nuance. We need a way to build up our understanding of these feelings and what they mean, and we can do that by being curious about ourselves.

A lot of who we are, our essential nature, is hidden from us. It lies hidden below a complex structure of beliefs, attitudes and stories that we acquired so early in life that we can’t remember.

-

At one level, the practice of inquiry is a simple process of checking in with yourself, but it goes well beyond the checking in you might do if someone just asked “how are you feeling?” Alexander Beiner, in “Rebel Wisdom’s Guild to Inquiry” describes it as “a process of coming into a deep curiosity with whatever’s happening or around a certain topic and not necessarily knowing what the answer is.”

-

Robert Brumet (robertbrumet.com) explains it this way: “The inquiry process always begins with your present moment experience. It can begin with a question or simply be an open inquiry of your present experience. If the inquiry is prompted by a question then hold the question in mind as you begin the process. Regardless the question, always explore your present moment experience. The purpose of inquiry is not to get an ‘answer’ in the usual sense but to simply use the question (or your present experience) as a starting point for your exploration. Let the question be open-ended; don’t become focused on getting a specific answer. Let the question be lived in the present moment.”

-

Because you’re not really looking for an answer to your question, inquiry is different than similar activities, like listening to your Intuition.

-

According to Robert Brumet, “The purpose of inquiry as a spiritual practice is to gain deeper insight and understanding into your own essential nature.” Along the same lines, the Ridhwan School website suggests that as we practice inquiry, “Over time, our experience is increasingly informed by innate qualities of our Being—love, joy, strength, will, compassion, and peace, among others—that have been hidden by unconscious beliefs and attitudes.” So, it would seem that Inquiry is intended as a way too get to know our “essential nature,” and to bring it more to the surface. In that sense, it’s a kind of training for Discernment.

-

Inquiry can be done alone or with another person: a witness. An important part of the practice is verbalizing your experience, so it can be very helpful to have someone that you’re speaking to. It’s been found that the struggle to express in words (communicating to self and others) what you’re feeling in the now can be a transformative experience.

-

As a witness of someone practicing inquiry, your task is to maintain a state of Mindful Presence. You want to listen without distracting them or interfering with them. This is different than what is sometimes called “active listening,” which often encourages the listener to make the speaker aware that they’re listening by mirroring them, nodding or making sounds. As Alexander Beiner explained in “Rebel Wisdom’s Guide to Inquiry,” “the invitation is, and the practice is to try and minimize [nodding and making sounds] as much as possible. You know, you don’t have to be a robot, but equally, it helps to just be in a state of witnessing presence. […] And that presence really helps the person inquiring to feel like they have time and space to go wherever they need to go.”

-

In the practice, you take a moment to become present—Mindfulness—then focus your attention inward and attempt to speak out loud how you’re feeling, both at an emotional level and in terms of felt senses. You might notice that you’re feeling agitated or that there’s a tightness in your chest, or maybe that you’re feeling open and relaxed. Alexander Beiner gives an example of the process:

“So for me, inquiry often feels like following lots of subtle threads almost like being a detective of my experience, or I’ve heard it said as almost like being a connoisseur of your own experience. And so, as I’m talking during inquiry, I might feel a certain sensation and the attitude of curiosity is maybe the most important quality to play with and cultivate because as something comes up, if curiosity sort of leads me toward a thread of ‘oh, okay I notice as I say that, I’m getting a slight… maybe a slight feeling of being a little bit detached, or I’m getting a slight feeling of something in my shoulder, I’m not quite sure what it is,’ and then I might go into that, and what often happens is that it transforms and it’s actually quite an exciting process because the curiosity, and kind of moving with those threads and following those threads usually leads me somewhere I really didn’t expect.”

- End the practice session when you feel like you’re done. Take moment to feel and express Gratitude to your witness if you have one, and you might want to write down some notes or insights in your Notebook.

Therefore:

Ask yourself a question and use the process of inquiry to explore your senses and emotions, accessing the subconscious knowledge they provide. Get to know yourself better by learning to recognize aspects of your essential nature.

Inquiry involves noticing the many aspects of your experience simultaneously: your emotions—Now I Feel—your Felt Senses, thoughts, mental state, and senses like your Sense of Hearing and your Sense of Sight, so improving your sensitivity to any of these will improve your Inquiry practice; it’s considered a practice that can enrich, but not replace, your Mindfulness practice;.