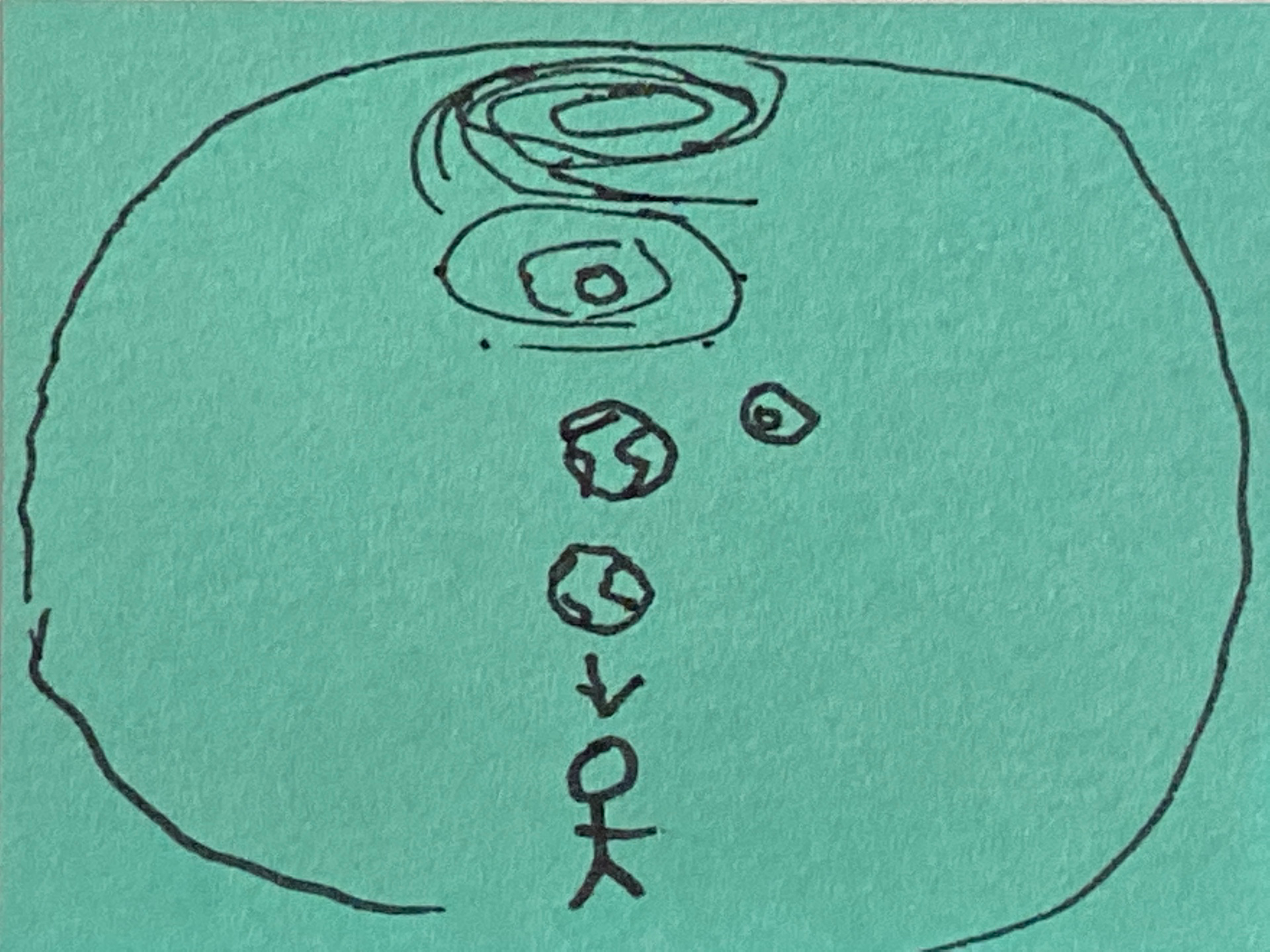

Start With Universe

Ensure you include all relevant aspects of a problem by starting with Universe.

when trying to understand a system, the scope of your understanding needs to be at least one level higher than the problem (e.g. to make a better house, look at the housing industry).

A solution that comes from too narrow an understanding of the problem is destined to be the source of new, unexpected problems.

-

“Start with universe” is a broad-to-specific, whole systems approach that Buckminster Fuller used to define the scope of a problem he was working on. His concern was that if we look at a specific, local problem and try to expand our attention outward from that point to find the causes and relevant factors involved, we’re very likely to miss something. Alternatively, if we start with literally everything (universe) and eliminate things that are irrelevant, we’re more likely to include all relevant factors.

-

When I first encounter this strategy, I was put off by what seemed like the infinitely large starting place that he was suggesting: universe. I couldn’t fathom how I was to start with something that is fundamentally impossible for our minds to comprehend as a whole. The answer is that universe itself undergoes a couple of major reductions before we even begin.

-

First, Fuller defined universe as “the aggregate of all humanity’s consciously apprehended and communicated (to self or others) experiences,” which when you get down to it means that universe is everything humans know about universe. That’s very helpful because it turns something that’s potentially infinite into something finite. For clarity, I call this version of universe “Humanity’s Universe” because it’s very specific to human experience. The universe of another species would arguably be very different, for example, “Dogkind’s Universe” would like contain a lot more experience of smell.

-

It’s worth noting that Fuller’s definition of universe also includes what we might consider our metaphysical experiences, such as our thoughts, imaginings, dreams, and our spiritual and religious experiences. Science has felt the need to exclude these kinds of experiences in its focus on the physical universe, but they’re clearly part of the human experience and are therefore part of Humanity’s Universe.

-

Second, there is no way that any one of us can know all of Humanity’s Universe, so we have to work with our portion of it: our Personal Universe. Our personal universe contains everything we know: all our direct experience, what we learned from those experiences, and all the stuff we learned in school, or on the news, or in books, or anywhere about other people’s experiences. That is the knowledge base, the universe, that we need to start with.

-

Ideally, this process would involve more than just your Personal Universe. If you go through this narrowing process with a group of people, you can benefit from many personal universes and get more coverage of Humanity’s Universe.

-

Depending on the problem you’re considering, you’re likely to have some gaping holes in your personal universe, so using this pattern will prompt you to do some learning. It’s a significant step toward becoming a Comprehensive Sensemakers.

-

As for the process itself, it’s both simple and harder than it sounds. The idea is to progressively divide universe into halves, what Fuller called “reduction by bits,” in reference to the binary math of computers where a bit has just two states: zero or one, off or on, no or yes. We do this by pondering the problem at hand and asking questions like you do in the game Twenty Questions: “is it physical or metaphysical?” “Does it involve phenomenon outside our solar system?” “Is it affected by solar radiation or lunar gravity (tides)?” “Is it self-contained or does it produce waste that is released into the environment?” And so on.

-

Fuller points out that “In four halving you have eliminated 94 percent of the irrelevant Universe. In seven halving you have removed 99.2 percent of irrelevant Universe.” Of course, these aren’t hard numbers because no “halving” of universe is likely to divide it into exactly equal parts, but they give you an idea of how quickly you can zero in on the problem.

-

The questions that you ask yourself are in many ways related to the answers you come up with for earlier questions. In my example above, I imagined a problem concerning energy generation, so the first answer was “physical.” Based on that answer, I proceeded with questions that further divide the physical universe. Had my imagined problem been something about learning, the answer to the first question would have been “both” because there are both physical and metaphysical aspects of learning. I would have had to devise other questions in order to divide universe meaningfully.

-

It seems clear that Fuller considered this to be an ongoing process, not something that you do once in phase one of solving a problem and then forget about. He sees it as an iterative or progressive process where coming up with a useful question and answer may take time, research and experimentation.

-

Clearly Fuller used Intuition in his process: “We depend entirely upon our innate facilities, the most important of which is our intuition, and test our progressive intuitions with experiments.”

-

If you’re doing this as part of a collaborative process, I highly recommend that you document the process by listing the questions and answers as you develop them so others can learn from or contribute to your thinking.

Therefore:

Ensure you include all relevant aspects of a problem by starting with Universe.

In order to access your Intuition, you might want to do this process in a state of Mindfulness or by using the practice of Inquiry